10 Years On: DaGrin, A Rapper Who Challenged The Single Story

“The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story.”

– Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, ‘The Dangers of a Single Story’

Many people don’t know he had an album that came before C.E.O. Of DaGrin, this is what they’ll remember: his face against a wall, frustrated, yet with eyes marked with the unmistakable glare of ambition.

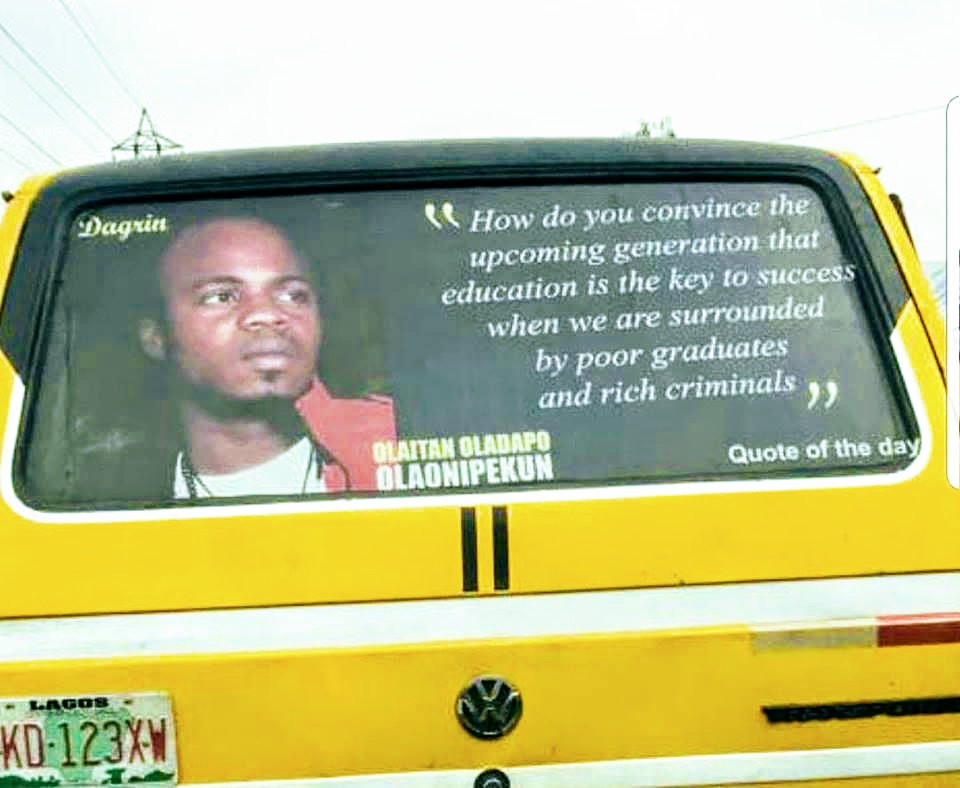

Nigeria leaves much to be desired. It is with the determination inspired by this space did he turned his gaze on a nation that has frustrated its people and continues to. Knee-deep in the reality of the streets, DaGrin, born Oladapo Olaitan Olaonipekun, was afforded a most valuable resource for an artist of his kind. When he rapped, his voice was boldened with the confidence of one who represents many who shared his reality. He donned that responsibility like a cape.

C.E.O, the album many came to know him by, became an indisputable classic; sweeping through Nigeria, its impact was unprecedented for rap delivered indigenously. Lord of Ajasa might have walked, but DaGrin definitely ran.

Then, at the onset of what seemed a unique path, on April 22nd, 2010, exactly ten years ago, the rapper was announced dead. He’d been in a car crash eight days before and had been hospitalized at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), where he drew his last breath.

The impact of his death was felt very fiercely. Circa 2010, I would walk past Ajegunle streets and see boys having a good time – alcohol, smoke, and all – while blasting DaGrin’s songs from their speakers, rapping each word triumphantly, though the pain of his demise was etched into every inflection. Endlessly, on radio channels, his voice scratched into immortality. On TV, celebrities wore their grief on black and sang a tribute which extolled the spirit of a man who climbed through insurmountable odds to get to the top. Interview. DaGrin was a good friend to me. Interview. DaGrin was a great rapper. Interviews, and then more interviews. All who had an opinion on his person and music spoke in glowing words. More songs on the radio and in the streets. The boisterous voice became the soundtrack of the times.

Many returned to C.E.O (Chief Executive Omo-Ita), a declaration of his position as a notable voice of the streets. As written on a posthumous review, “[the album] created the blueprint for what is now celebrated and commercialized as indigenous rap. While not directly inspirational for this generation of stars, it created industry-changing realizations about the potential inherent in this brand of locally generated Hip-hop”.

His place in Nigerian Hip Hop is thus untouchable. DaGrin’s death might have elevated him to godly status, but there’s no doubting the stylistic patterns in Nigerian rap he took and elevated. For even the non-Yoruba listener (like me), his raps resonated. Infusing English and its Nigerian variant into his lyrics, he managed to pass a sense of what he was saying. So, when I memorized most parts of “Kondo” back in secondary school, I rapped its words knowing I was talking about being some way with a girl. It would be years before I would ask a friend to translate some sections of the song, to which I laughed like crazy. Whew.

Olamide who, over the course of his career, has drawn comparisons to DaGrin, delivers his raps similarly, especially in the breakout years of his career. Many fans of the older rapper couldn’t see past the stylistic similarities, less informed on the fact that music is no man’s personal property. With consistent years of releasing hit songs and balancing his Pop appeal with his rap roots, Olamide is being mentioned in the same breathe as one of the greatest to ever do it, rap or Pop. Sometime last year, both acts trended in a series of back-and-forth on Twitter. It had been nine years since DaGrin died. The pull of his story, however, ensured he had a cult following, and they sought to even raise his name even higher. Olamide, by now arguably the greatest indigenous rapper ever, holds a position DaGrin would have ascended, were he alive, they believed. He had the lyricism. He had the hits. He had the personality. And like many stories led by wistful recollection, his was a great story, made even greater by the circumstances which trailed his death: the conspiracies, the reports of poor healthcare, his supposed foreboding of his own death on a song.

What can be made of that is that, ten years later, DaGrin’s still remembered. For a people that has grown into the most distracted generation ever, that’s a feat in itself, and speaks to the man’s influence and legacy. The rise of street hop which has become a leading staple for Nigerian consumers cannot be removed from Omo-Ita’s trailblazing efforts.

We moved to Ajegunle in 2009, my family and I. Color me acne-faced, shy, and curious in the ways shy kids were. I asked questions of my world. And because it was the Ajegunle of African China’s “Crisis”, my early days were spent walking, looking, for burnt houses and riotous scenes.

I would rather find a youth culture steeped in poverty, of the mind and otherwise. 10-year-old me couldn’t see a brilliance past the Ugo C. Ugo textbooks I’d learnt to almost perfection. Young people hung at dark corners, playing music, smoking and drinking. At times, I’d lean close, but not too close for their notice. The wild conversations had me piqued, but there weren’t folks I’d listen to for life advice or ‘serious’ talk. In Kirikiri Town where we lived prior to a downward spiral in my father’s fortunes, we lived in a 3-bedroom flat and I attended one of the best schools around. I was basically an Ajebutter.

Eleven years later, that has changed. I would trace that to the positions being flipped in 2016. I was among the boys who hung at dark corners. But unlike what I thought, the conversations we had were actually enlightening, much to the confusion of my 10-year-old self. We talked music, football, movies – basically anything which had anyone’s interest. But more than chatter for its fun, we talked of life. Of its uncertainties, its beauty, what we hoped to get out of it. Nigeria hung like a huge shadow above us, like it did above DaGrin and the boys he must have hung in dark corners with, boys he must have kicked a freestyle with.

And that’s why I write these words, why I relate to DaGrin’s story, ten years after his death. Being the one who made it out comes with its depression – they call it Survivor’s Guilt. A writer wondered why DaGrin would make a song like “If I Die” when he’d made it as an artist, and was had the world at his feet to conquer. I wonder if DaGrin thought of how people he knew could be stuck in the ghetto which holds little for dreamers. I wonder what was on his mind as he drove that April day. Wonder if the sky cast an ominous cloud over the world. Rumors have it he was drunk. Or maybe he was deep in thought. Who knows?

But here’s one thing I know: that the artist is cursed. He’s cursed to feel everything more intensely. He’s cursed by the desire to always understand and control a reality. He’s grievously cursed with the frustration that comes with the realization that he can’t.

Veteran music journalist, Ayomide Tayo (popularly known as AOT2), who wrote a detailed and emotional report about the day of DaGrin’s death, conceded that “[the artist] was a special rapper to me”. Another piece by him linked the rapper’s death to the birth of the NET magazine, an outlet which rose to prominence in the last decade for its robust sense of music journalism.

“His art”, he says in a voice recording he sent to me: I’d asked of his relationship with DaGrin’s music. “We’ve had rap in Nigeria since the early 80s, we’ve had songwriters and rappers. We’ve had Junior and Pretty, the Trybesmen, Mode9, and others, but DaGrin…” His voice was laden with emotion.

“He was not the progenitor of indigenous rap but what DaGrin did was he made it a very verifiable art form. That’s the first thing. He told stories of inner-city life. People that Hip Hop, surprisingly, in Nigeria, hadn’t reached out to. M.I and Naeto C came with their personalities. Especially Naeto, who was about that flashy life, high taste.

“What DaGrin did was he took rap into the ghetto. And that was huge for me, coming from a middle-class background. What he rapped was true, because we’ve seen it in the streets. When he raps of a man stealing from his wife, I know it’s true, because I’ve seen it”, Ayomide Tayo said.

DaGrin’s bravery, the respect he got from his contemporaries, while “putting out a new style of rap content” spoke to Ayomide Tayo’s own journalistic ambitions, what he sought to achieve with his pen.

He was also a subject of the journalist’s keen interest. “It had never been done in this level, where the flow is flawless, the project is gritty, AOT2 said. So obviously, that intrigued me. He had the story, he also had the flair, and he definitely had the music.”

Ten years after, we remember DaGrin. When we think of him, we don’t see a man bedridden for eight days, waiting to die. We think of a man who wanted to bless the earth with his physical essence as long as his human body let him.

A mouthpiece of a generation, part of his relevance stems from the sociopolitical concerns of today’s Nigeria, not quite removed from that of the man who would have been 35 today. But there’s a streak of hope in the sadness which underlies much of this story. That for his 25 years on earth, DaGrin made his name thunder. That for every one of those years, his character formed an arc that would remind many of glorious their existence was, irrespective.

He was a man who embraced the complexity of his character. And many of us today have him to thank for being a part of our own awakening. I know I do.

One response to “10 Years On: DaGrin, A Rapper Who Challenged The Single Story”

Dagrin was one of those talented Nigerian Afrobeat artist that changed the narrative of Nigerian music and Afrobeat itself.

With that said, its good to note that Nigeria, Africa and the World that now consume Afrobeat shall never forget a hero an icon and a legend REST on KING!

We miss you and love you forever